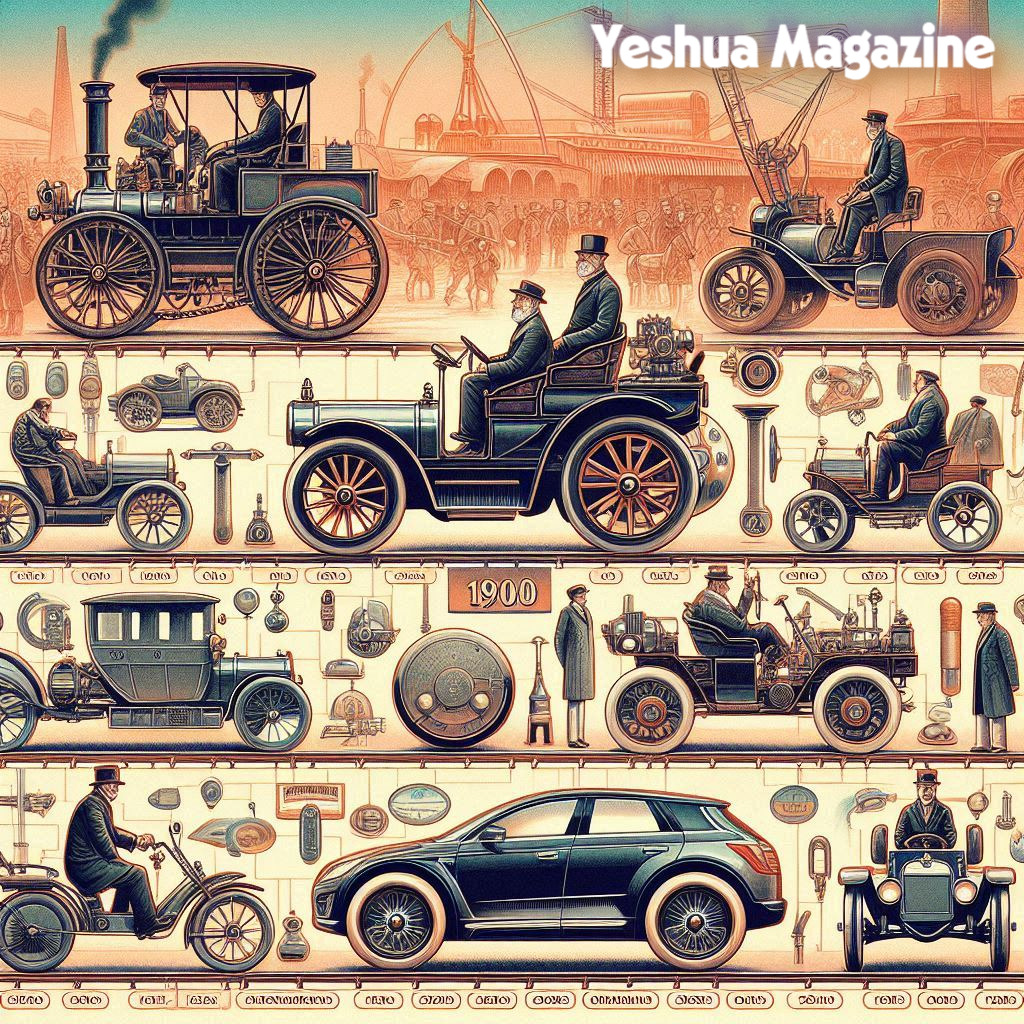

Discover the true history of who invented the car. From steam-powered carriages to the Benz Patent-Motorwagen, explore the complete evolution of the automobile and the key inventors behind it.

Who Invented the Car? The Complete History of the Automobile’s Evolution

The question “Who invented the car?” seems simple, but the answer is a fascinating journey through centuries of innovation, rivalry, and incremental genius. Unlike the light bulb or telephone, the automobile has no single inventor. It is the culmination of thousands of advancements across mechanics, engineering, and materials science. To trace its origin is to move beyond the simplistic myth of a single “Eureka!” moment and instead follow a timeline of pivotal breakthroughs, from clunky steam-powered carriages of the 18th century to the gasoline-powered revolution that defined the 20th. This article unravels this complex history, giving credit where it’s due and separating legend from fact to reveal how humanity arrived at one of its most transformative inventions.

The Early Pioneers: Steam Power and the “Auto-Mobile” Concept

Long before gasoline, inventors were captivated by the idea of a self-propelled vehicle—an “auto-mobile.”

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot (1769): The First Self-Propelled Road Vehicle

A French military engineer, Cugnot built the “Fardier à vapeur” (steam dray) in 1769. This three-wheeled, steam-powered tractor was designed to haul artillery for the French Army.

- What it was: A massive, cumbersome vehicle with a copper boiler mounted over a front wheel. It could reach about 2.5 miles per hour but had to stop every 15 minutes to build up steam pressure.

- Why it matters: It was the first machine to successfully convert steam power into rotary mechanical motion for land propulsion. It proved the concept was possible, though it was impractical and famously crashed into a wall—arguably the world’s first automobile accident.

Throughout the early 1800s, British engineers like Richard Trevithick and Walter Hancock refined steam carriages, creating operational “road locomotives.” However, they were heavy, slow to start, required a constant water supply, and faced fierce opposition from railway and horse-coach lobbies, leading to restrictive legislation like Britain’s infamous “Red Flag Act” (which required a man with a red flag to walk ahead of vehicles). This effectively stalled automotive progress in Britain for decades.

The Critical Precursor: The Internal Combustion Engine

The true automobile required a lighter, more efficient power source. This emerged not from transportation engineers, but from scientists tinkering with engines.

- 1860: Étienne Lenoir (Belgium) built the first commercially successful internal combustion engine, running on coal gas. He mounted it on a rudimentary vehicle that traveled about 11 miles, but it was inefficient and stationary engine applications.

- 1876: Nikolaus Otto (Germany) made the revolutionary leap with the first practical four-stroke engine (intake, compression, power, exhaust), known as the “Otto Cycle.” This design remains the foundation for most car engines today. Otto’s engine was stationary, but it provided the essential blueprint.

The Breakthrough: Karl Benz and the Patent-Motorwagen (1885-1886)

While others were making engines, a German engineer, Karl Benz, was working on an integrated vehicle. In 1885, working independently in Mannheim, he completed the “Benz Patent-Motorwagen Nummer 1.”

In January 1886, he was granted German patent number DRP 37435 for a “vehicle powered by a gas engine.” This is widely regarded as the birth certificate of the automobile.

Why the Benz Patent-Motorwagen was the “First True Car”:

- Integrated Design: Benz didn’t just put an engine on a carriage. He designed a complete, lightweight, three-wheeled vehicle from the ground up, with the engine, chassis, and drive mechanism working as one system.

- Key Innovations: It featured a single-cylinder four-stroke engine (958cc, 0.75 horsepower), an electric ignition, a carburetor for fuel evaporation, a water-cooling system, and a differential gear for the rear wheels.

- Purpose-Built: It was designed from the start as a passenger vehicle for personal transportation. In July 1886, Benz made the first public test drive, covering about 1 kilometer.

- Commercial Production: Unlike one-off prototypes, Benz began series production in 1888, making it the world’s first commercially available automobile.

The Unsung Heroine: Bertha Benz

In August 1888, without Karl’s knowledge, his wife Bertha Benz took the Model III Patent-Motorwagen with her two sons on the world’s first long-distance road trip—approximately 106 km (66 miles) from Mannheim to Pforzheim to visit her mother.

This daring act was more than a joyride; it was critical field testing. She improvised repairs (using a garter to insulate a wire, a hatpin to clear a fuel line, and pharmacy ligroin as fuel), proving the car’s practical utility and generating invaluable publicity. This trip demonstrated the automobile’s potential beyond a short-range novelty.

The Parallel Inventor: Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach

While Benz was developing his integrated car, another brilliant duo was working separately: Gottlieb Daimler (a former colleague of Otto) and Wilhelm Maybach. Their focus was different but equally transformative.

In 1886, the same year as Benz’s patent, they mounted their small, high-speed, four-stroke “Grandfather Clock” engine onto a horse-drawn carriage, creating what is considered the world’s first four-wheeled motor vehicle. Their contribution was not the vehicle frame but the lightweight, high-RPM gasoline engine that made automobiles faster and more practical. Daimler is famously quoted as aiming to motorize all forms of transport: “on land, on water, and in the air.”

The Benz vs. Daimler Rivalry

For years, Benz (focusing on integrated car design) and Daimler (focusing on powerful engines) were direct competitors in Germany, unaware of each other’s work at first. This rivalry fueled rapid innovation. In 1926, the two companies merged to form Daimler-Benz AG, which produces Mercedes-Benz vehicles to this day.

The American Chapter: From the Duryea Brothers to Henry Ford

The automotive spark quickly crossed the Atlantic.

- 1893: Charles and Frank Duryea built and operated the first successful gasoline-powered car in the United States. The Duryea Motor Wagon Company became America’s first car manufacturer.

- Ransom E. Olds pioneered the concept of the assembly line with his Curved Dash Olds in 1901, becoming the first mass-produced, affordable American car.

- But the true revolution came with Henry Ford. While he did not invent the car or the assembly line, he perfected and scaled them. His Model T (1908) and the moving Highland Park assembly line (1913) reduced production time from 12.5 hours to 93 minutes per chassis. This slashed the price, making cars accessible to the average American and transforming society, economy, and landscape. Ford’s genius was in manufacturing, not invention.

So, Who Really “Invented the Car?” A Multi-Layered Answer

- For the first self-propelled road vehicle: Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot (1769, steam-powered).

- For the first practical internal combustion engine: Nikolaus Otto (1876, four-stroke cycle).

- For the first purpose-built, patented, gasoline-powered automobile: Karl Benz (1886, Benz Patent-Motorwagen).

- For the first four-wheeled auto with a high-speed engine: Gottlieb Daimler & Wilhelm Maybach (1886).

- For making the car a universal commodity: Henry Ford (1908-1913, mass production).

The Global Evolution and the Electric Ancestor

It is also crucial to note that in the late 1800s, electric vehicles were serious contenders. Engineers like Thomas Parker in England (1884) and Ányos Jedlik in Hungary (1828, with a small model) built early electric vehicles. In the 1890s, electric taxis were common in cities like New York and London because they were quiet, clean, and easy to start. They lost out due to limited battery range and the proliferation of petroleum infrastructure—a trend only reversing in the 21st century.

Conclusion: An Invention of Many Fathers

The automobile is a quintessential example of a simultaneous invention—an idea whose time had come, nurtured by the Industrial Revolution’s advancements in metallurgy, machining, and fuel science. Its story is not of a lone genius but of an international relay race spanning over a century.

Karl Benz holds the strongest claim for creating the first true car as we recognize it: a complete, integrated, gasoline-powered vehicle designed for personal transport and patented as such. However, to credit him alone erases the essential contributions of Cugnot’s proof-of-concept, Otto’s engine, Daimler’s powerplant, Bertha Benz’s fearless validation, and Ford’s democratizing vision.

The car was not invented; it was evolved. It is a rolling monument to human ingenuity, a machine that reshaped the world by shrinking distances, creating industries, and granting unprecedented personal freedom. Its history reminds us that great breakthroughs are rarely singular events, but the culmination of countless smaller innovations, failures, and triumphs on the road to progress.