Introduction: The Cosmic Highway System

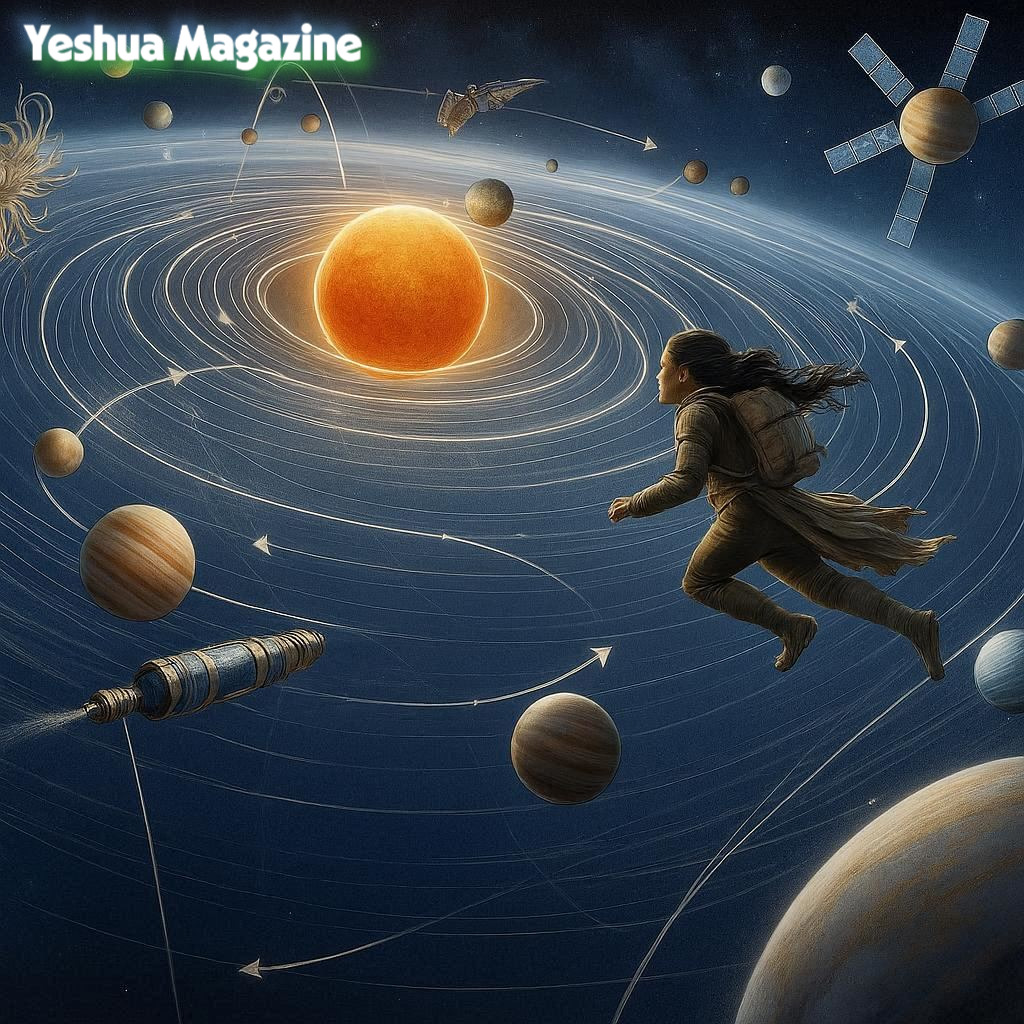

Spacecraft face a unique challenge. They must cross vast distances with very limited fuel. Instead of flying straight, they use the solar system’s own gravity. This turns planets and moons into cosmic slingshots.

Isaac Newton’s 337-year-old laws make it all possible. These laws create an “interplanetary superhighway.” It is a network of gravitational pathways. Spacecraft ride this network to reach distant worlds. A tiny error can mean missing a target by millions of kilometers. Mastering these invisible paths is the key to exploration.

Part 1: Gravity Assists – The Celestial Slingshot

The Physics of a Free Speed Boost

A gravity assist seems to break intuition. A spacecraft gains speed without using its engines. How? It steals a tiny bit of a planet’s orbital energy.

Here’s the process:

- The spacecraft approaches a planet from behind.

- The planet’s gravity pulls it in, bending its path.

- As it swings around, it takes some of the planet’s speed.

- It shoots away faster than it arrived.

The planet’s speed drops by a tiny, unnoticeable amount. The spacecraft gets a huge boost.

The Math Behind the Maneuver

The speed gain depends on two things:

- The planet’s own speed around the Sun.

- How sharp the turn is around the planet.

Jupiter provides the strongest boosts. It is massive and moves quickly.

Famous Uses of Gravity Assists

The Voyager missions are the classic example. They used a rare alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. This alignment happens once every 176 years.

Voyager 2 used each planet’s gravity to reach the next. This saved years of travel time and enormous amounts of fuel.

The Parker Solar Probe uses Venus for gravity assists. It will fly by Venus seven times. Each flyby brings it closer to the Sun. It will eventually reach record speeds.

Part 2: Hohmann Transfer Orbits – The Efficient Path

The Most Fuel-Saving Route

In 1925, Walter Hohmann found the most efficient path between two orbits. It is an elliptical orbit that touches both the starting and destination orbits.

Think of a Hohmann transfer as a cosmic “on-ramp.” It uses the least fuel but takes more time.

The Journey from Earth to Mars

- A rocket gives the spacecraft a precise push near Earth.

- It enters an elliptical orbit around the Sun.

- It coasts for about 8 months.

- Near Mars, it fires engines again to match the planet’s speed.

The Launch Window Problem

Planets are always moving. The starting and destination points must align perfectly. For Earth and Mars, this alignment happens roughly every 26 months. This is why missions to Mars launch in clusters.

Part 3: Lagrange Points – Nature’s Parking Spots

The Five Balanced Points

Mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange found five special points. In any two-body system, gravity and motion balance perfectly here. Think of the Earth and Sun, or Earth and Moon.

These points are labeled L1 through L5.

- L1: Between the two bodies. Perfect for solar observatories.

- L2: Behind the smaller body. The James Webb Space Telescope orbits here.

- L4 & L5: 60 degrees ahead and behind in the orbit. These are stable zones. Asteroids called “Trojans” are often found here.

Why They Matter for Exploration

Lagrange points are strategic rest stops.

- L2 is a prime location. The James Webb Space Telescope sits at Sun-Earth L2. Here, it can keep its shield toward the Sun and Earth while observing the cosmos.

- They are gateways. NASA’s future Lunar Gateway station will orbit near the Moon-Earth L2 point.

- They can be interconnected. A path linking Lagrange points of different planets creates a low-energy highway. This is called the Interplanetary Transport Network.

Part 4: Navigating a Chaotic System

The Three-Body Problem

Newton solved the motion of two bodies. Add a third, and the math gets messy. There is no perfect, long-term solution. This is the “three-body problem.”

For spacecraft, this means trajectories can’t be perfectly predicted. Tiny errors grow over time.

How Mission Control Copes

- Constant Tracking: NASA’s Deep Space Network watches spacecraft constantly.

- Course Corrections: Missions plan for small mid-course engine burns to fix their path.

- Extra Fuel: Spacecraft carry backup fuel for these unexpected corrections.

Computers to the Rescue

Modern missions rely on supercomputers. They simulate millions of possible paths. They find the best route through the gravitational chaos.

For example, the BepiColombo mission to Mercury uses nine planetary flybys. Its complex path was only possible with advanced computing.

Part 5: The Future of Space Navigation

Sailing by Starlight

Future probes may navigate by themselves. They could use signals from pulsars. Pulsars are spinning neutron stars. They flash with incredible regularity, like cosmic lighthouses.

By comparing signals from multiple pulsars, a spacecraft could find its position. This technique has already been tested on the International Space Station.

AI Pilots

For missions far from Earth, communication delays are too long. Future spacecraft will need AI pilots.

These AI systems will:

- Identify planets and stars with onboard cameras.

- Calculate new trajectories in real-time.

- Make decisions without waiting for commands from Earth.

FAQs: Your Navigation Questions Answered

Q1: Why can’t spacecraft fly in a straight line?

A: They could, but it would require impossible amounts of fuel. Gravity assists provide the extra speed for free.

Q2: How accurate are these maneuvers?

A: Extremely accurate. The Cassini probe’s final Titan flyby was within 1 kilometer of its target after a 7-year journey. That’s like hitting a bullseye from across a continent.

Q3: Can you get a gravity assist from any object?

A: The boost depends on the object’s mass and speed. Jupiter gives a huge push. An asteroid gives almost none. You need a massive, fast-moving planet for a major assist.

Q4: What happens if the calculation is wrong?

A: Mission teams plan for errors. They track the spacecraft and can fire small engines to correct its path. The worst case is usually just using more backup fuel.

Q5: How do spacecraft know where they are?

A: They use a mix of tools: radio signals from Earth, pictures of stars, and images of planets. It’s like high-tech celestial navigation.

Q6: Could we use a black hole for a gravity assist?

A: In theory, yes, and the speed boost would be incredible. But the dangers—like being stretched apart—make this pure science fiction for now.

Conclusion: Dancing with Gravity

Spacecraft navigation is a silent ballet. It turns gravity from a force that binds us into a highway that frees us. Each successful mission proves the timeless power of physics.

These principles guided Voyager to the stars. They will guide humans to Mars. As we venture farther, this dance with gravity will continue. It is our passport to the cosmos.